In football, “ideologies” always fluctuate according to the circumstances. Bahia fans – like any fan of a club from the Northeast – have always been staunch critics of the system of financial inequalities that have harmed the club in recent decades, something that decimated its much-believed protagonism after the 1988 title.

Now owned by the largest, richest and most sophisticated multi-club network on the planet, the City Football Group, a conglomerate literally controlled by a state, Bahia fans will obviously be offended by any proposal for financial regulation.

Especially if it comes from people linked to some big club in Rio de Janeiro or São Paulo, and even more so if it comes from another one. powerful-but-not-as-powerful-as-us American billionaire owner of a multi-club chain. How it happened.

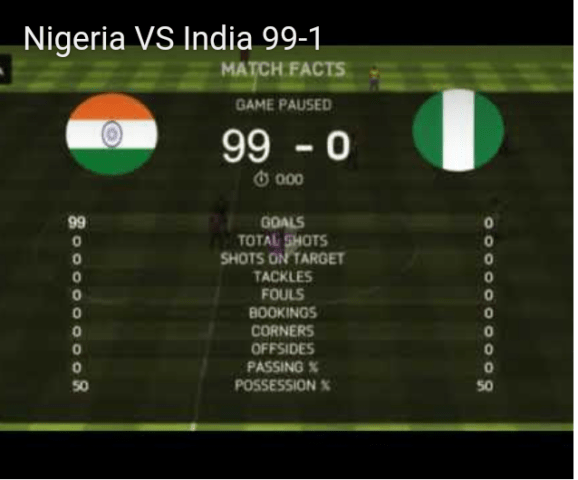

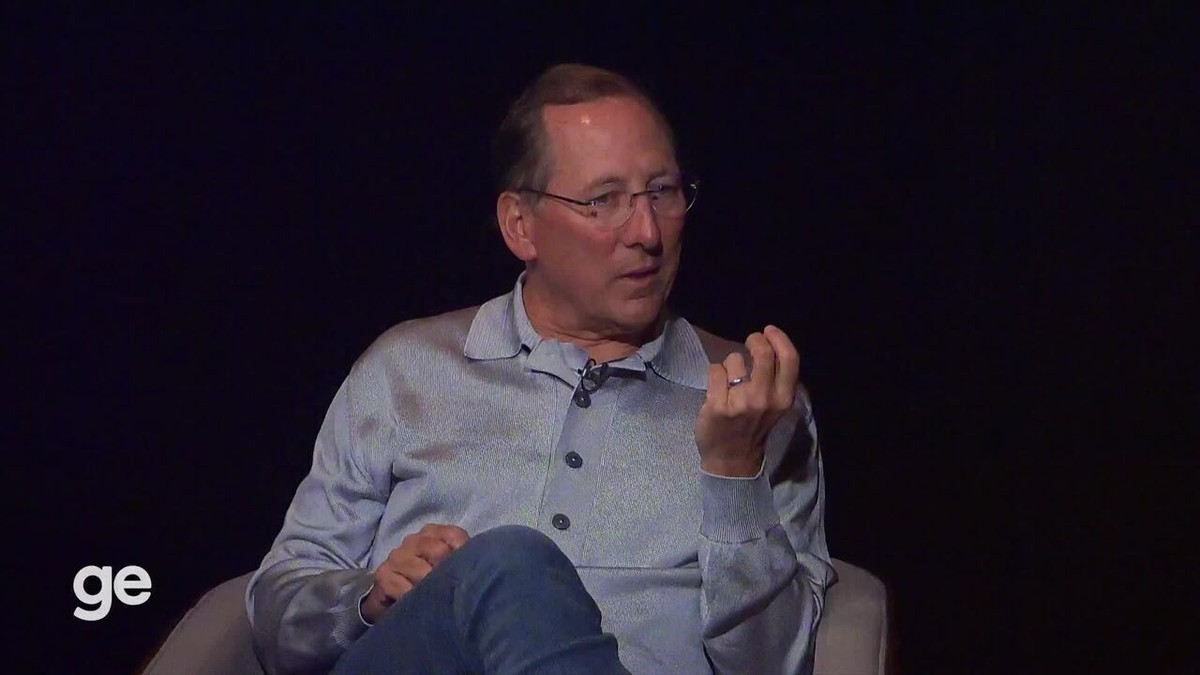

In an interview with GE, John Textor, owner of Botafogo’s SAF and the multi-club network Eagle Football Holdings, said: “This is my warning to Corinthians, Palmeiras, Flamengo… If we don’t do something, we will wake up in 70 years, under the current administrative structure, with the people who are here today, Bahia will win the Brazilian Championship in 17 out of every 20 years”.

“They are Abu Dhabi (…) I am competing with a country, not an owner. A model of unbridled spending, without restrictions,” Textor said shortly after. See below:

“If we don’t do anything now, Bahia will win 20 championships in a row”, says Textor

Suggestions of financial fair play – or salary caps, as John Textor suggested in an interview with GE – are absolutely nothing new. Ten years ago, UEFA created its own financial control system, and later each league created its own internal model, with some substantial differences.

The most sophisticated and rigid model is that of the Spanish La Liga, something that has already been discussed on this blog. In force for ten years, the “Squad Cost Limit” imposes on local clubs an advance control of expenses, which considers the club’s revenue capacity as a parameter for combined costs related to transfers, agents’ commissions, athlete remuneration, coaching staff salaries and even women’s football. Read more details here.

The “salary cap” is not a common reality in football in general, but it has existed for a long time in North American sports leagues, which have structural models that are completely different from the “European model football” we are used to (federative, pyramid of divisions, relegation/promotion, etc.).

“Fair play” x “salary cap”

Whether it’s the NBA, MLS or NFL, American sports have been used to a system where the league itself is a closed company for almost a century. The dozens of participating teams are mere “franchises” of this large company, belonging to different owners, but always subject to strict rules established by the parent company, the “league”.

Historically, considering the financial disparities between the main North American urban centers – there is a population, economic and structural gap between Los Angeles and Milwaukee –, and although highly commercialized since its beginnings, North American sport has always been guided by regulations capable of guaranteeing greater sporting balance and, consequently, greater financial sustainability for franchise owners.

As a result, there are usually rules that limit the amounts paid to athletes according to their history, which ensure that different franchises can have top athletes in their squads and that young athletes are not harassed by competitors. These measures ensure greater competitiveness and commercial attractiveness for the league (although there are always loopholes that favor some franchises).

That is why John Textor wants a “salary cap”, not a “financial fair play” (FPF) system, which he has been treating for some time as a system of “maintaining the status quo”. Although this is a somewhat unfair definition of the purpose of the mechanism, what has in fact been noted over the years is that the FPF has generated a hardening of financial power relations as a side effect.

But “fair play” was created as a measure to preserve the financial sustainability of clubs, not necessarily to ensure sporting balance. What was happening? In the late 2000s, there were many cases of European clubs going bankrupt, being administratively relegated or being abandoned by their owners due to high debts.

At the other extreme, this is a period of unprecedented entry of new types of owners: American billionaires, Russian oligarchs, Asian tycoons, Arab sheikhs and sovereign wealth funds from the Persian Gulf.

Although we are talking about different origins and approaches among them, in the end almost all examples of this generation of new investors were guided by the use of football clubs for political purposes. This means that it did not matter much how much money was “lost” in football, because the ultimate goal was to convert the sporting gains into political capital, to clean up the image and to establish “new friendships” in Europe.

For FIFA and UEFA this would not be a big problem. More money in football, better salaries, higher commissions, higher amounts in international transfers. Money is money. But money also has relative value. The side effect of this huge flow of money was an unsustainable wage hyperinflation for the vast majority of clubs – that is, those that were not “blessed” with an owner interested in using the club as a propaganda instrument. READ FULL STORY HERE>>>CLICK HERE TO CONTINUE READING>>>

Financial fair play therefore emerges as a mechanism to curb this trend of hyperinflation and unsustainability in the football production chain. Clubs could only spend something close to what they were able to collect from broadcasting rights, player sales, membership plans (or season tickets), ticket sales, sponsorships and other commercial lines.

This logic, however, limited the ability of many owners to inject new capital directly – as has always been the case in football, which is accustomed to patronage schemes. Investors in smaller clubs, with little or no international projection, always found themselves at a great disadvantage against the already consolidated super-clubs.

That is why criticism of “fair play” is so consistent among investors in emerging clubs. Meanwhile, powerful funds took advantage of loopholes to continue standing out: they began using other companies they owned to pay inflated amounts for sponsorships, camouflaging the injection of resources that “fair play” sought to limit, by presenting them in their balance sheets as conventional revenues.

The “home sponsorship” move is something that has been happening ever since with clubs owned by sovereign wealth funds, as John Textor himself states:

– “We have to compete against Qatar [PSG] in France. I am competing with a country, not an owner. A model of unbridled spending, without restrictions. As long as they can generate enough revenue, and they can because of the relationships with Qatar and the sponsorships. Then they can put the revenues exactly where they need to, to spend what they want because they want to win the UEFA Champions League.”

Although there is much talk about the City Football Group, and it is already in Brazil through the Bahia SAF, it is not the only multi-club network with “state funding”. Neighboring countries that are equally theocratic have developed their own networks, later being inspired by the conglomerate model developed by Abu Dhabi (UAE).

The emirate of Qatar, which hosted the last World Cup, has owned Paris Saint-Germain since 2011. It began expanding the operations of Qatar Sports Investment (QSI), buying a minority stake in Portuguese club SC Braga. QSI is a direct subsidiary of the Qatar Investment Authority, the Qatari sovereign wealth fund. Several QSI companies have sponsored PSG. QSI representatives have already indicated their intention to expand the network in the coming years. Brazil, as is known, could be one of the destinations.

Much newer, much richer and much more threatening than these two, Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund has also entered the game. The Public Investment Fund (PIF) caught the attention of the entire planet last year when it nationalized the four biggest clubs in the Saudi league, injecting fortunes and signing top-tier football stars such as Cristiano Ronaldo, Karim Benzema, Sadio Mané and Neymar Jr.

The PIF had recently taken over ownership of Newcastle United FC at the time, after fighting a long battle for approval of the purchase within the Premier League – achieved after an arrangement in which the Saudis appeared as mere members of a consortium that involved two other investment funds (PCP Capital and RB Sports).

Once owners, the PIF selected four different companies it owned to act as sponsors of Newcastle United: STC, Sela, Noon and Saudia. One can imagine how this impacts the club’s financial fair play calculations when the “revenues” are analyzed.

Amanda Steveley, a representative of this consortium, has revealed on several occasions the intentions of forming a multi-club network. But not in the conventional way, which is slower and more laborious. The group saw itself acquiring or becoming partners in already established networks – to the point that the acquisition of 777 Partners was speculated at the time.

If the big Brazilian clubs and businessman John Textor are worried about the possibility of City Football Group pouring money into Bahia, they may not have yet considered the scale of the impact that a network like the Saudi PIF would have on unregulated Brazilian football. On a scale that may incite pro-regulation positions among Bahia and City’s own fans.

The “salary cap” devised by John Textor has precedent, and may not fit perfectly into the Brazilian system, but it has a fair purpose. The big question is whether Eagle Football Holdings would be in favor of such a measure if there were no City Football Group, or if CR Flamengo did not raise more than R$1 billion so easily.

And vice versa and vice versa. After all, “ideologies” always fluctuate according to circumstances.

2024-07-17 20:20:04

#Salary #cap #Bahia #City #understand #John #Textors #idea #irlan #simoes #blog

Related